White Folks Still Don't Get the MLK Day

3 Ways to Celebrate the King Holiday

It can be tempting for us as white people to assume that the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday isn’t really for us.

Out of a desire not to misrepresent King, or out of a well-intentioned attempt not to colonize his legacy, we may decide the best thing to do is to sit the day out. We tell ourselves that King Day belongs to Black Americans, and that our most respectful posture is to step aside and let others mark it on their own terms.

There is wisdom in resisting the urge to center ourselves. But opting out entirely isn’t the same thing as being faithful. In fact, there are ways white people can participate in Martin Luther King Jr. Day that honor the man, respect those who are more culturally connected to his legacy, and still take our own responsibility seriously.

Here are three.

1. Listen to what King had to say to white people

One of the most faithful ways white people can observe this holiday is by actually listening to King’s words addressed directly to us.

The most obvious place to begin is Letter from Birmingham Jail. King wrote it explicitly to white moderates. These were white leaders who believed in order over justice, who preferred gradualism to disruption, and who underestimated the urgency of injustice in their own time.

King had a clear and challenging perspective on the role white people played in movements for justice. We still can lean into his thoughts on this. When we treat King Day as a cultural moment that doesn’t include us, we miss the opportunity to wrestle with those teachings.

There is no faithful reading of King’s life or work that suggests his legacy was meant to be honored only by Black Americans. King believed white people had something to learn, something to relinquish, and something to offer. But only if we were willing to be formed by his message rather than sentimental about it.

For white people, King Day is not primarily about celebration. It is about learning—especially learning who we are in the story of justice, and who we are being called to become.

2. Resist what he resisted. Be for what he was for.

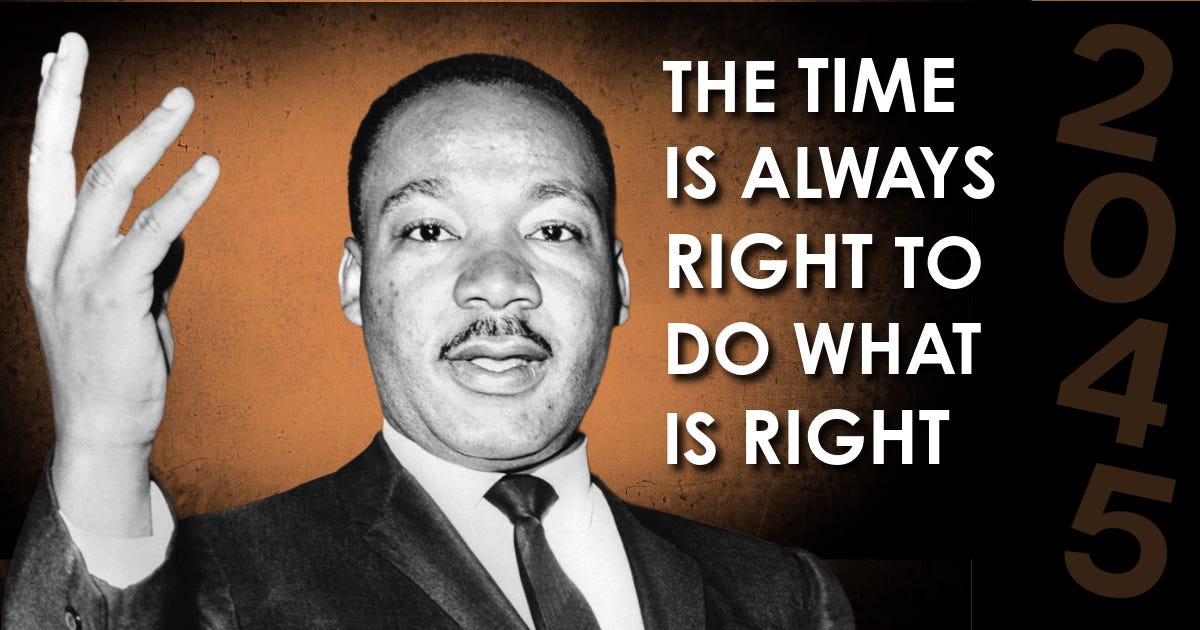

The truest way to honor Dr. King is not through quotes or ceremonies, but through commitment.

King did not limit his concerns to race alone. He named what he called the “triple evils” of racism, materialism, and militarism, and he understood them as deeply interconnected. He spoke out against the Vietnam War. He addressed poverty and labor conditions. He imagined what he called the Beloved Community. This vision was not merely racial harmony, but a society oriented toward the common good.

I cannot imagine a faithful reading of King’s life that would exclude white people who want to work against those evils. At the same time, King was clear that our role was not primary. At one point, King observed that there was a time when Black Americans needed white people to stand for them because of the imbalance of power. But he insisted that in his own time, Black Americans were fully capable of leading their own struggle. The role of white people, he said, was secondary and supportive.

That distinction matters.

3. Live His Courage in Our Time

It’s normal for white people to love King now. It was not normal to be white and love King when he was alive. That distinction matters more than we often admit.

Today, affirming Martin Luther King Jr. costs very little. His words are safely canonized. His image is softened. His legacy is taught in fragments that emphasize unity while muting disruption. Supporting King low requires no real social risk. It rarely strains family relationships, friendships, church memberships, or professional standing. In many spaces, it actually confers moral credibility.

But that was not true in the 1950s and 60s. White people who aligned themselves with King were often viewed as agitators, traitors to their community, naïve idealists, or dangerous radicals. Supporting him meant risking social exile, economic consequences, and sometimes physical harm. To love King then was to be out of step with the dominant moral consensus of white America.

Which raises a harder question for today: If supporting King is easy now, what is the equivalent difficulty in our own time?

What are the causes that carry real social cost today. The ones that make people uncomfortable at dinner tables. The ones that threaten donor relationships, institutional stability, political access, or personal safety. The ones where “waiting for a better moment” sounds reasonable, even wise.

History suggests that the moral clarity we grant King now was not available in real time. It had to be chosen against pressure, fear, and ridicule. Which means our admiration for King is incomplete if it does not provoke a similar question of courage.

If we want to honor those white people who stood with King when it was abnormal to do so, the question is not whether we would have supported him then.

The question is who we are willing to stand with now, while it is still costly.

Our move

There is a fine line between honoring King and turning him into a reflection of our own progressive self-image. White people are often tempted to imagine ourselves as the heroes of the story, rather than as people being invited into humility, discipline, and solidarity. Martin Luther King Jr. Day is not about centering ourselves. But neither is it about opting out. It is an invitation to remember, to listen, and to live differently.

I’m convinced white people have yet to fully embraced King Day as a moment of moral formation. But the invitation is still here.